There is something about the way I tell history stories that makes people say: “I don’t believe that happened. Mark must have made up that story.” People often tell me that they check out my stories on Google because they don’t believe them. Have you ever checked out one of my improbable stories?

“I am the President of France.” In May 1920, President Paul Deschanel of France was traveling on his presidential train. During the night, as the train was passing Orléans, south of Paris, Deschanel opened the window of his sleeping car, leaned out too far, and fell out of the window. He suffered only minor injuries from the fall, remarkable for a man of 64. Deschanel walked up to the nearest person, a track inspector and said: “Don’t be alarmed. I am the President of France.” He was wearing nothing but his pajamas. The track inspector assumed the man was drunk and replied: “Certainly you are, and I am Napoleon Bonaparte.” The track inspector took Deschanel to his house and called a doctor. The doctor confirmed that the man actually was the president of France to the astonishment of the track inspector. When the story was published in French newspapers, Deschanel became a national laughing stock and was forced to resign.

European history might have played out very differently if Deschanel had not fallen out of the window of his sleeping car. In the French presidential election earlier in 1920, Deschanel ran against Georges Clemenceau, the principal author of the Treaty of Versailles. Deschanel was a critic of the treaty. He won in a landslide, ending Clemenceau’s career. Deschanel wanted to renegotiate parts of the Treaty of Versailles with the new German government, but those plans came to an end with his resignation. Deschanel worried that a future German government might remilitarize the Rhineland, placing troops right on France’s border. Clemenceau argued that there was no need to worry about that since the treaty prohibited Germany from ever placing troops in the Rhineland.

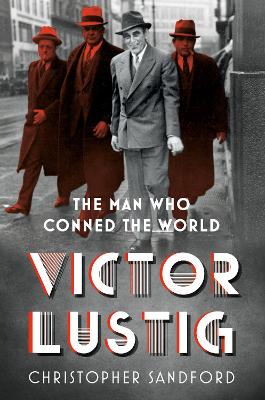

The Man Who Sold the Eiffel Tower. Victor Lustig was the most successful swindler in history. In the 1920s, Lustig sold the Eiffel Tower to wealthy businessmen. Lustig impersonated a French government official. He told scrap metal dealers that the French government was going to tear down the Eiffel Tower and sell the steel for scrap. He convinced these businessmen to pay him huge sums of money for the Eiffel Tower. The French police were aware of what Lustig was doing, but they were unable to prosecute him because his victims refused to testify against him. Lustig’s victims were prominent businessmen and did not want to look like fools in court. Eventually, the French government issued a warrant for Lustig’s arrest, but Lustig escaped to the United States just ahead of the police. In the United States, Lustig invented new swindles. Lustig talked Al Capone into investing $50,000 in one of Lustig’s scams. This was a very risky thing for Lustig to do. $50,000 was a huge amount of money in the 1920s, and Al Capone was a very dangerous person to play for a sucker. However, Al Capone never found out that Lustig had conned him. I wonder if this story was the inspiration for the movie ‘The Sting.’ It sounds very similar.