As you may know, I enjoy telling history stories that sound so improbable that people assume that I made them up. The Pastry War is one of those stories. How did the United States get California from Mexico? Believe it or not, it was because somebody swiped some French pastries from a bakery in Mexico City in 1832. In 1832, a French pastry chef named Monsieur Remontel wrote a letter to King Louis-Phillipe of France. Monsieur Remontel stated that he owned a small bakery on the outskirts of Mexico City and that one day, some Mexican officers looted his bakery and stole his pastries. Monsieur Remontel asked the king to force the Mexican government to pay him 60,000 pesos for the stolen French pastries and damage to his shop. This was a wildly inflated valuation of the pastries. Back in those days, a Mexican peso was a large silver coin. It contained just under 1 ounce of silver. 1 peso was a day’s wages in Mexico City. This means that Monsieur Remontel was claiming that the damage to this pastry shop and the stolen French pastries were worth 50,000 ounces of silver. That was, of course, preposterous. How could the inventory of a French pastry shop have been worth 50,000 ounces of silver? The appraised value of the bakery itself was under 1,000 pesos.

The Pastry War. The story of the stolen French pastries was widely circulated in newspapers across France. In 1838, King Louis-Phillipe of France demanded that Mexico immediately pay France 600,000 pesos for a long list of dubious claims, beginning with 60,000 pesos for the stolen French pastries. The Mexican government couldn’t have paid France 600,000 pesos even if they wanted to. They didn’t have 600,000 pesos. So, the king of France ordered the invasion of Mexico. Below is a painting of the Battle of Veracuz, in which the French navy bombarded the city’s fort, reducing it to rubble. The commander of the French fleet, Admiral Baudin, then threatened to open fire on the city itself unless the Mexican government immediately agreed to pay France 60,000 pesos for the French pastries. The Mexican government had no choice but to agree, thus ending the Pastry War. However, the Pastry War also led to Santa Anna becoming the dictator of Mexico again. Santa Anna had ruled Mexico before, but after losing the War of Texas Independence, Santa Anna had been forced out of power. After becoming dictator of Mexico as a result of the Pastry War, Santa Anna once again pursued disastrously bad foreign policies with the United States, which led to the Mexican War, which Santa Anna also lost. Santa Anna was a terrible general, but he didn’t know it. He called himself the “Napoleon of the West.” Well, that is how the United States got California, Arizona, Nevada, and Utah; and parts of Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico. However, that wasn’t the end of the Pastry War.

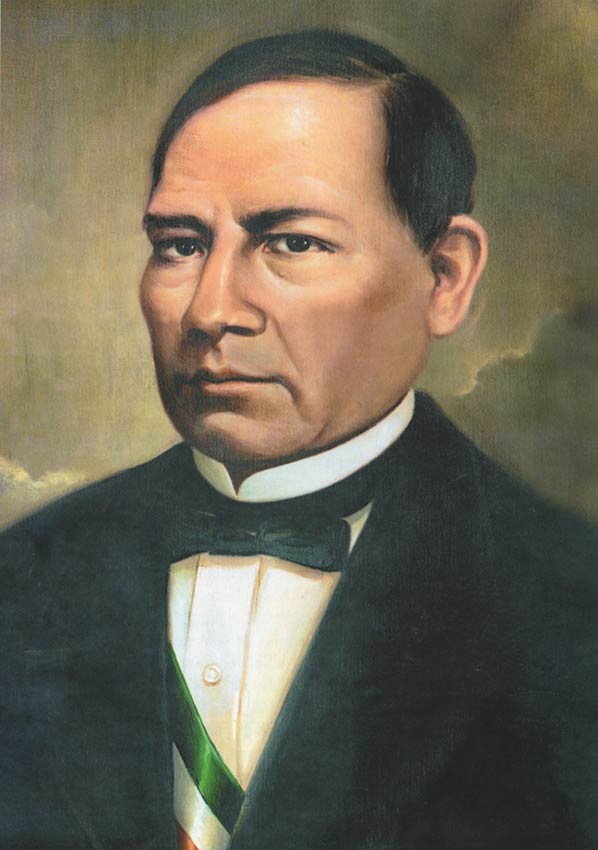

The Second Pastry War. (aka The Second French Intervention) Even though the Mexican government had agreed to pay France for the stolen French pastries, they never did pay for them. As the years passed, the amount of money that France claimed that Mexico owed them grew enormously because the French kept adding interest to the debt and at very high rates. In 1861, France invaded Mexico again, ostensibly to collect the debt. Emperor Louis Napoleon of France installed an Austrian duke, the Emperor Maximilian, as head of a puppet government in Mexico City. In this second war, France had powerful allies. Many European countries sent armies to Mexico to help the French collect the money. In addition to the European armies, several thousand Confederate soldiers also fought for France. However, this time things were different. Santa Anna was gone, and Mexico was now led by President Benito Juarez, an astute politician and military strategist. The Second Pastry War was much bloodier than the first. Over 50,000 Mexicans were killed in the second French intervention, including over 10,000 Mexican civilians who were simply shot by the French. However, this time the French lost the war and were forced out of Mexico for good, and the Mexicans executed Emperor Maximilian. Hostilities between France and Mexico continued even after the French army left Mexico. Mexico had still not paid for the stolen French pastries. In 1880, the French government finally accepted that this nonsense had gone on long enough and dropped their demand that Mexico pay for the French pastries that were stolen almost 50 years earlier. I think this story illustrates how a stubborn and arrogant government can allow a small incident to spiral out of control. That has happened many times in history. Now – be honest – you’ve never heard of the Pastry War before, have you? I have never met a Mexican history buff who had ever heard of the Pastry War before, and there are a lot of Mexican history buffs here in California. I wonder how many of you are going to look up the Pastry War on Google to see if I made up this improbable story.